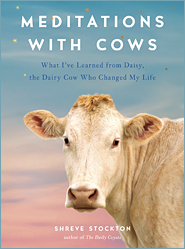

Do cows smile?

Yes. Often while meditating.

A Spoonful Of Sugar

If you’ve never used a soup spoon to feed blackstrap molasses to a six-foot-tall, horned steer in the dead of winter, I highly recommend adding this to your bucket list. It is tricky: to fill a cold spoon with cold molasses; to navigate the spoon around the steer’s foot-long tongue and into his mouth; to dodge his sticky lips as he searches your face and torso for another spoonful. Both parties end up happy messes by the end of it.

It’s been unbelievably icy around here this winter. I wished I had crampons this morning just to cross the driveway to the chicken house. The snow drifts melt and puddle during the warm days, then it all re-freezes overnight. Ice upon ice upon ice. Some of the ice is smooth and slick, and some of it looks and feels like rough crumbles of glass. From this ice, Frisco got tiny cuts in the bottom of his feet, in the soft area around the actual hoof, and bacteria entered and caused an infection called foot rot. Foot rot is serious and painful, though not nearly as gross as the name implies. It’s fairly common in cattle, but this was my first first-hand experience with it. The infection caused swelling in both his hind ankles and made him lame – lameness, from the pain of the infection, is the most obvious early sign of foot rot. It can be knocked out with antibiotics, and cows have been known to fight the infection on their own, without medication, over the course of a couple of weeks, but a bad case can be fatal. This all started the last week of December, and it has been a battle.

The worst thing about doctoring large animals is the sheer volume of medicine one needs to administer in each dose. Giving a cat or a rooster a shot requires the tiniest syringe, a fine, delicate needle, and the act of giving the shot is over in a fraction of a second. Quick and painless, at least for the one administering the shot (ME!). With animals that weigh in well over 1000 pounds, it’s a very different story. Pills the size of a roll of quarters, syringes just as large. Giving a steer that is too tall to fit in the squeeze chute six giant pills and three giant shots multiple times a week is decidedly less fun than feeding him molasses with a spoon.

This bolus pusher helped me out with the pills. You put one pill in the tube at the end, then stick the apparatus into the beloved bovine’s mouth, guiding it in as far as you can and over the bump that cattle have at the back of their tongue, and then, with your third hand, push the plunger which gently deposits the pill so far back that they can’t spit it out and have to swallow it. Repeat six times. The pills annoyed Frisco, but at least they didn’t hurt. There’s just no gentle way to give a shot. Halfway through Frisco’s treatment, after I’d been dutifully cleaning the needles after each use, I came across a series of photos of a needle after reuse. I used fresh needles from then on, but I think it’s time I learned how to sharpen a needle.

While sick, Frisco lost his appetite and lost about 250 pounds with it. Just when I felt he had turned the corner and knocked out the infection, we got hit with serious cold and a few negative-20-degree nights. I stressed about his weakness and weight loss in such cold, but he and Daisy and Fiona slept together in the barn, and their body heat (which is substantial, and the original reason I started napping on cattle so many years ago) kept Frisco warm.

Yet Frisco needed to gain back some weight – and quickly. I was trying to think up some sort of high calorie mash I could give him, and landed on organic blackstrap molasses. I pretty much force-fed him by the spoonful the first day, but it did immediately stimulate his appetite for hay, and on the second day, he was like, “that stuff is delicious, do give me more.” The third day, I mixed the molasses with organic barley in a big pan. I don’t usually give my bovines grain, but Frisco desperately needed the calories, and this confection really helped him gain back his strength and his appetite. I gave him this treat once a day for a week or so, and now he’s getting it every other day. He’ll be bummed when this tapers off and his only treat is dried alfalfa pellets.

Friday morning, things were looking good. Frisco had a hearty appetite and dove into the breakfast hay alongside Daisy and Fiona. Around noon, I took Frisco his molasses treat and finally felt he was out of the woods. His personality was back in full force, and instead of losing weight daily, I could see he had started to gain some back. Hallelujah! I took my first full breath in two weeks, turned to Fiona, and my breath caught halfway down. Something was very, very wrong. She wasn’t showing signs of foot rot; she was showing signs of labor. I spent the afternoon and evening at the corral, and at dusk, Fiona miscarried. I think the only thing worse than midwifing a miscarriage would be having one. I really don’t have anything else to say on it. If you’ve been through it, you know; if you haven’t, words can’t possibly approach it.

This story actually ends on a high note, beyond Frisco and Fiona remaining alive and on the mend. My vet came by on Saturday because Fiona had not birthed the placenta (apparently, it can take up to a week with cows with preterm calves; he made sure she wasn’t carrying twins and gave her some shots to help the process). After he attended to Fiona, I asked him to preg test Daisy. Daisy’s last calf was born in July 2012. It was a treacherous birth, extremely hard on Daisy and the calf did not survive. We got Maia, an orphan calf, for Daisy to adopt (and Maia is now all grown up and pregnant herself!) but Daisy has not bred back since. I’ve had her preg checked a few times during the last 18 months but can’t even remember the last time – late spring or early summer – and on Saturday, I had zero expectations, even though I’d not seen Daisy and Sir Baby “courting” since October. But since the vet was here, and Daisy was underfoot, why not?

When the vet said, “90 days,” I thought he meant no dice, and that he’d check her again in 90 days. I think he had to repeat himself three times for it to finally register, and when it did, I wept. She’s 90 days bred! If all continues to go well, she’ll calve mid-July. After nearly two years, and wondering if Daisy would ever be able to get pregnant again, this news was the sweetest sugar that helped soothe the sadness.

A Daisy At My Door

The OK Corral

The last I wrote about the Farmily was the tragic loss of Daisy’s newborn calf. Thank you to everyone who expressed concern for Daisy ~ I didn’t even address that side of things because it was too sad for me to write about ~ Daisy loves being a mother. I did what I could to minimize her loss by making sure she had companionship ~ Sir Baby has been in one section of the corral since his injury, as confinement is an important part of his healing process, and I had Daisy in another section of the corral for the week leading up to her due date so I could keep a close eye on her. Since I wanted to continue to monitor Daisy and since Baby is healing so well, I opened up the two sections in the corral so that Daisy and Baby were together, and we brought in the ancient matriarch cow, who is over 20 years old and a total badass, and one orphaned calf, whose mother died this spring, to join Daisy and Sir Baby in the corral.

The Matriarch was part of the Special Project cows who roamed the home place, but since it’s been so dry, we moved the Special Project bunch, including Fiona and Frisco, to grassier pastures just down the road. Though the matriarch can get around surprisingly well, trailing her to the new pasture with the rest of the group seemed a bit much. She has been a strong, gentle presence in the corrals with Daisy. The orphan calf has been weaned for two months since he lost his mother, but I had hopes that he and Daisy might connect. Unfortunately, he wasn’t at all interested in milk anymore. The most essential part of making an unmatched cow-calf pair is the calf’s drive to nurse. You can help manipulate all the other elements, but you can’t force that. When I saw that connection was futile, I told my vet that I was looking for a bum calf ~ it’s not the season for calves, but one never knows what might pop up and my vet is hooked into everything.

But back to Sir Baby and Daisy for a moment. For new readers, I bought Daisy from a dairy. She’d calved about three months before I got her, so she was in milk, and she was bred back (pregnant with Frisco). Cows are mammals, not machines, and must have a calf annually in order to make milk. Dairy protocol is to remove the calves from their mothers immediately (veal is a “by-product” of the dairy industry), so Daisy had never raised a calf when I got her. I was pretty overwhelmed with milking when I got Daisy, and I wanted a bum calf to help me with the excess milk. A neighbor happened to have a freakish love triangle occur with some of his cows ~ one cow had a calf, and all was normal. Then another cow had twins and accepted one of them, which is also normal. The first cow abandoned her calf and adopted the other twin! Very weird. But it was fate. That abandoned calf was Sir Baby. I still remember going to pick him up and sitting with him in the backseat of Mike’s truck on the ride home. Daisy was NOT interested in being a mother when I introduced them; she didn’t know, she had only been milked by machines, and then by me. But baby Sir Baby was determined to nurse, and after about a week, Daisy clicked into motherhood and she and Sir Baby still have an incredible bond to this day ~ they are family. In the days following her calf’s death, I’d often find Daisy licking Sir Baby’s neck and shoulders, tending to him as her first son, and the connection they share seemed to really help Daisy with the absence of her newest calf.

My vet called me on Thursday afternoon announcing he had a calf waiting for me to pick up. Buying bum calves at the sale ring is risky business because you generally don’t know what their first hours and days were like ~ how was the birth? Did they get colostrum? So many factors can affect whether a calf becomes a strong, healthy youngster or expires early, as proven with Daisy’s calf. But the stars aligned in this case ~ a rancher brought two dozen “cull cows” to the sale barn on Wednesday night for Thursday’s sale. Some of these cows were pregnant, and one of them had her baby that night, between midnight and 6 am. Cull cows are generally fine cows, just older ~ as I’ve written before, most ranchers sell their cows when they reach a certain age. Older cows are generally excellent mothers, so it’s likely this calf nursed and got her first dose of colostrum right after the birth. My vet bought the calf for me before the sale began, and I’m grateful beyond words that this cow’s last act was to provide Daisy and me with her beautiful baby. I had given my vet a gallon of Daisy’s colostrum as a thank you for coming out in the middle of the night to help with Daisy’s breech birth, so she was bottle fed Daisy’s colostrum throughout the day until Mike and I got there to pick her up.

Daisy was less than thrilled. Cows have very strong instincts to not allow any calf but their own to nurse ~ doing so would jeopardize their own baby, and this instinct carries even when that baby dies. So, twice a day, I put Daisy in the head catch with a bunk full of gourmet hay and let the calf drink her fill before I milked. A head catch is not a torture device ~ it’s a levered metal apparatus that closes around a cow’s neck but doesn’t actually touch her. Cow’s necks are wide when viewed from the side but incredibly narrow when viewed from above. The head catch has two curved panels that close around the cow’s neck but leave a hole ~ if you touch your pointer fingers together and your thumbs together, this is the shape of the hole it leaves. It’s not tight against the cow’s narrow neck but she can’t pull her wide head through the opening. I use this every day when I milk; it keeps Daisy comfortable but relatively still.

I wasn’t worried about this routine lasting forever, as Daisy and I went through this exact process with Sir Baby when he was a calf ~ at first, Daisy would only stand for him in the head catch, but after about a week, something switched inside Daisy and he was HERS. And today, that switch happened again. I went to the corral this morning and saw that one of Daisy’s teats was already pulled down (all the milk in that quarter had been drunk) and the calf was full and dozing. We have a love match! The calf is amazing ~ she adored Daisy from the start ~ and she’s huge. At one day old she looked like she was a month old, and now at a week old she looks three months old. She has her health, she has a new mother, and now all she needs is a name!

You Win Some. You Lose Some.

Daisy calved Saturday night ~ she had a breech birth and it was hard and horrible and I thought I might lose her. My vet came out to assist and, against all odds, the calf was born alive.

He was up and nursing after the birth, and bouncing around the next morning, nursing on one of Daisy’s front teats as I milked the back ones. But he started failing that evening, and though we did everything we could, he died two days later.

What can you say about a baby calf who died? {Who knows the book whose first line I just slightly altered?} I can’t really scream and cry about things being unfair, because in the last six weeks, Sir Baby and Daisy have been thisclose to death and pulled through beautifully. But it’s still terribly sad.

« go back — keep looking »