The Long and Winding and Beautiful and Tragic Story of 3M ~ Part II

When Mike and I returned to the barn an hour later, both Roxy and her calf were standing and the calf was trying to nurse. It can be challenging for a newborn to figure out how to balance and find a teat at the same time and the inevitable fumbling drives me crazy to watch. I know I should give calves time to figure it out on their own, and I try to keep my distance, but it’s so hard to watch a tiny, hungry baby suck on a teat sideways or fall right past a teat (over and over) or finally grasp a teat in their mouth just to have their mother turn to admire or lick her new baby and that movement swings the teat away and the fumbling begins anew. Sometimes I can’t help but intervene.

I crouched next to Roxy and her calf and guided a teat into his mouth and he latched on, and Roxy stood perfectly still while her calf had his first meal. Mike and I sat together in the hay, still overwhelmed from the breech delivery, and watched the simple beauty of Roxy nursing her calf. “How many people get to experience this in their lives,” I wondered to Mike. He didn’t know. I didn’t know this kind of life existed fifteen years ago.

Because the breech birth was hard on Roxy and because I wanted to watch her calf closely for any sign of illness or respiratory issues, I kept both of them in the barn for monitoring. Roxy’s udder was large for a heifer due to Daisy’s genetics – not enormous, but she had more milk than her newborn could drink. That evening, after her calf had drank twice and her udder still looked tight, I decided it would probably be best for Roxy if I tried to milk the two teats her calf hadn’t touched.

I usually freeze Daisy’s leftover colostrum – the rich “first milk” mammals produce – to have on hand for orphans or twins. It’s imperative that calves get colostrum as soon as possible and no later than 48 hours after birth, and I like to keep a stash on hand. This year, I got no colostrum from Daisy because of the medication she was given after her miscarriage – I dumped everything I milked for a week until the medication was out of her system.

Roxy had let me rub her udder before she calved – she loves attention and being brushed and when I rubbed her udder, she would raise her hind leg to encourage me to scratch that hard-to-reach spot where her leg meets her body. So, with her calf lying in the hay in front of her, I crouched at Roxy’s belly and, ready to leap away should she kick, tentatively began milking. Roxy stood perfectly still! She stood calmly and chewed her cud and I think she was grateful to have the pressure in her udder relieved. I milked over half a gallon of colostrum from her back teats.

The next morning, Roxy’s calf was running circles in the barn and bucking little baby bucks as calves do, but Roxy had a bulge of fluid under her belly skin and her udder was tight and the texture was very strange, almost like clay. Google told me this was udder edema and that it’s common in dairy heifers freshening (making milk) for the first time. Roxy fit this profile and all symptoms. The cure is to make sure the cow is completely milked out twice a day. Luckily Roxy was so easy to milk. She was even easier than Daisy had been this winter. I simply sat down beside her and she stood for me without food or halter or head catch, requiring nothing from me but gentleness and conversation.

* * *

Unlike other ranchers, Mike and I keep our cows until they die of old age. Most, if not all, ranchers sell their mother cows, usually when they reach the age of 8 to 12, and these culled older cows are replaced in the rancher’s herd by young heifers. From a business standpoint, this makes perfect sense – as cows age, their fertility drops off and, just like elder humans, elder cows tend to require more care: they need special consideration, nutritional supplements, more medical attention, more of the rancher’s time. All of this is money. And when the cow isn’t having calves, she’s not “paying her way,” so to speak (in terms of business). There’s no income to balance the expenses of food and vet bills and time.

Older cows sold into The System are treated like garbage. They’re considered “canner grade,” and are turned into pet food or fast food. These cows have little value (again, in terms of the status quo capitalist business model) and are treated as such. Mike started his herd by buying ten ten-year-old canner-grade cows, because they were cheap and what he could afford. They all had calves the next year, his herd grew, and all ten lived out the rest of their lives with Mike. Mike and I refuse to sell our older cows into The System. We feel they deserve the respect of living out their days in peace and comfort. Our little herd is half animal refuge, and we always have a handful of very old Grandmother cows at any given time.

Two days after Roxy calved, I glanced out the window at a cow walking up the driveway. “That cow is going to calve today,” I said to myself, and took a closer look to see who it was so I could keep track of her. It was 6, our most elder cow, and there was no way she was going to calve because there was no way she was pregnant. She was nineteen. She had broken her leg last year and it healed rather well, but she was very slow getting around. She was so, so bony – extremely underweight due to her age – and she creaked when she walked. “Oh,” I said to myself, “it’s just 6,” and I put it out of my mind.

I don’t know what it is I see, when I look at a cow and know she’s going to calve – it’s something in their posture that I can’t explain or point out to anyone. It’s that subtle noticing that begets knowing that Gavin De Becker talks about in The Gift of Fear (in a completely different context), of perceiving information that you can’t articulate and this is called instinct or intuition. I’ve learned to trust it. But in this instance, I must have caught 6’s hobbling out of the corner of my eye and interpreted it wrong, because 6 was not going to calve.

Mike came home a few hours later and saw 6 lying off by herself and thought, “Oh no, is she going to die today?” And when he went out to check on her an hour later, he turned on his heel and came to get me. 6 had calved. 6 had a baby! 6, our ancient, bony grandma, had given birth to a beautiful, perfect little calf, smaller than average but not by too much, and lively and healthy, already up and prancing around her mother. I still don’t understand how it was physically possible for 6 to grow a baby inside her in her condition – by all measures it was impossible. Her baby was truly miraculous.

6 did not have any milk. This is no surprise – she gave all her resources to her calf and had none remaining with which to produce milk. But she doted on her calf – she got up and licked her calf’s entire little body and let her calf suck her empty teats. I made a bottle of Roxy’s colostrum and 6’s calf gulped it down. She wanted more. I’d milked Roxy that morning as part of our twice-daily treatment for udder edema, but not since, so I led 6’s calf to the barn and put her in with Roxy. While most cows will kick at a calf who is not their own if it tries to nurse on them, sometimes heifers are more flexible (to the point of it being detrimental if they allow thieving calves to take all their milk at the expense of their own calf).

I pet Roxy and positioned 6’s calf beside her. I rubbed Roxy’s udder and squeezed her teats like I was going to milk her, and then let the calf take over. I wasn’t sure how Roxy would respond and was prepared to milk her into a bottle and feed 6’s calf that way if need be. But Roxy stood, and I brushed her while 6’s calf drained Roxy for me and had a satisfying first meal. When the calf finished, I took her back out to 6, who had made her way to the front of the barn. 6 licked and licked and licked her calf, and the two of them lay down side by side. Mike put panels up around the front of the barn to make a little corral around them, and I put a small trough in with them and filled it with water, and we gave 6 extra hay. She was going to need help raising her calf, and Roxy and I were going to do it.

There is so much more to this story.

Part III is here.

The Long and Winding and Beautiful and Tragic Story of 3M ~ Part I

Roxy, Daisy’s youngest daughter (not counting Mara), had her first calf this Spring. In the week leading up to Roxy calving, I had been watching her like a hawk. Since she is Daisy’s daughter and half her genetics are dairy cow, it’s harder to tell when she’s getting close to calving by looking at her udder. When an Angus cow’s udder fills out and loses all wrinkles, calving is nigh. But with Roxy, her udder looked full and ready and then it kept on growing. So I checked on her constantly. We always keep an extra close eye on heifers because they tend to need more help during or immediately after calving than older cows; it’s their first time, after all. And I tend to keep an extra close eye on all my cows whenever I can, because birth is a big deal, the culmination of months of growth and care, and birth can be life or death. One little thing or big thing goes wrong, and it all ends before it can begin.

Two days before she calved, I put Roxy in the barn so I could check on her more easily, especially at night. It was days away from a new moon, and finding her at midnight or 3am took luck and wandering the hills and flats of the property with the weak light of a flashlight, searching for where she was sleeping. When it’s as dark as it is without moonlight, you have to stumble right on to a cow to see her. I had more success finding clusters of sleeping cows by sound rather than sight, listening for their collective deep breaths in the dark, huffs of sighs, their great exhales. Once I found a group, I had to shine my light on every body to find Roxy before returning to bed. Cows in labor prefer to go off by themselves and find a secluded place to have their calf, and this is why I finally put Roxy in the barn. Searching for her in the dark, if she decided to go off alone into a draw or far corner to have her baby in the night, would have been nearly impossible.

This year, I have put off going into town until it is absolutely unavoidable. There’s just been too much going on at home to take care of, and town is thirty miles away, and errands are never something I look forward to, even in the mellowest of times. I’ve been averaging one trip every three or four weeks, and by mid-April, it had reached the point where I simply had to run to town. I coordinated with Mike. I would check on Roxy mid-morning, then go to town for a few hours. He would be home by noon to feed cows and would check on her then. I would be home soon after to resume my post of obsessively watching her. I got home around 1:30pm and went straight into the house with groceries, and as Mike and I were chatting, I went out on the deck with binoculars to peek at Roxy in the barn. I could barely see her, but something about her posture sent off every alarm in my head. “I think she’s calving,” I said as I ran past Mike and dashed out to the barn. Mike was right behind me. When we got to the barn, we saw she was in labor, and her calf’s hooves were already out, and her calf was breech.

You can tell if a calf is breech or not by the hooves when they emerge. When a calf is in the ideal position, the shiny black part of their hooves is facing up. These are the front hooves, and the calf is positioned like it is diving out of its mother – front legs, then face, then the rest of its body. When a calf is breech, the soft white undersides of its hooves are facing up. The calf is in the same ‘diving’ position, but backwards – the hind legs come out first, and you are looking at the soles of its back hooves. We saw the white bottoms of the hooves and Mike went straight into denial. “Maybe it’s just twisted around and looks backwards,” he said. Since Roxy is tame and trusts me, I walked up to her, pet her back, and reached my hand inside her, following the leg of her calf. “I feel the hock,” I said to Mike. The hock is the pointy joint on the hind legs of cows (and cats and horses and many other four legged animals) that does not exist on the front legs. “I’ll call the vet,” I said, and we ran back to the house. The vet’s receptionist said he was in the field and wouldn’t be available till 5pm. Babies don’t wait, and this one was coming now, and Mike and I had no choice but to deliver it.

The reason delivering breech births is so stressful is because if you do it wrong, the baby will die. When a baby is delivered, a pressure change occurs when the thorax emerges, and this is what compels the baby to take its first breath. (Tangent – this is so bizarre to observe in non-breech births, when the calf’s front legs and face and entire head are out of the cow, and its eyes may be open, and sometimes it hangs out like this for a while if the cow needs to rest, and it’s not breathing!) So, if the thorax is delivered before the baby’s head, as is the case with breech births, this biological demand to breathe will still take place, and the calf will take its enormous first breath at that moment. And if the calf’s head is still inside its mother, it will not be able to breathe air and it will drown or suffocate – in either case, it will die.

What makes breech births in cows so hard to deliver successfully is that the two main ‘hang ups’ during delivery are the calf’s hips and shoulders. These are the widest parts of the calf, by a significant margin. Depending on the size of the calf and the experience of the cow, she may need time to push these parts out. This is why I’ve seen the strange scenario I described above so many times – a calf with its front legs and head out for several minutes before the cow delivers the shoulders and the rest. With a breech, there can be no waiting. Once the hips are out, the torso slithers out quickly because it is so much narrower, and the person delivering the calf must get the shoulders and the rest of the calf out immediately or the calf will start breathing while its head is still inside the cow and it will die. Breech births require human assistance because the cow just can’t do this fast enough on her own for the baby to survive.

And it was up to Mike and me. We got the chain and the calf puller, which is a huge T-shaped bar that fits against the hind legs of the cow, with notches in the long part of the T and a ratchet handle. I grabbed leather gloves and a towel, because baby calves are incredibly slippery, and we would need something with a little traction if we had to pull by hand. Out in the barn, I put the chain around the calf’s ankles. It’s a rounded chain that fits around their ankles just above the hooves and doesn’t hurt the calf. A chain must be used as the point of contact because the force required to pull a calf in an emergency is so great and calves are so slippery; there’s no other way I’ve heard of to pull one out. We crouched beside Roxy where she lay in the barn and hooked the chain to the calf puller. Then Mike started ratcheting out the calf, slowly, working only when Roxy pushed on her own.

Mike and Roxy delivered the calf’s hips by working together, with me coaching Mike, telling him when to ratchet with Roxy’s contractions and when to stop. And then everything went so fast and so crazy and also felt like eternity. The calf’s hips emerged and the thorax slithered out faster than I thought possible. Mike hit the wall of the barn with the puller bar and didn’t have room to ratchet out the shoulders. We each grabbed a calf leg with both our hands and pulled with all our might, me screaming “we have to get it out NOW!” and somehow, together, we did. I immediately thrust my hand down the calf’s throat and scooped out a handful of jelly-like liquid as the calf blinked and gasped and shook his head.

We did it.

I was nervous for Roxy because it was hard on her and I was nervous for the calf because I wasn’t positive it hadn’t breathed any liquid. I was worried that pneumonia would show up in a few days and that Roxy’s calf would die within a week. But for now, everything was good. We placed the calf right at Roxy’s head so she didn’t have to get up in order to lick him clean, and left them together to rest while we returned to the house to have our delayed-reaction heart attacks.

Roxy’s calf is not 3M. This is just the beginning.

Part II is here.

Things I Would Post On Twitter….

….. if I could stand opening Twitter anymore:

• I was traversing a new pasture on foot and found myself face to face with a baby fox. We stood perfectly still and silent and stared at each other for… five minutes? I have a poor concept of time as it is, which goes completely out the window when in the presence of baby foxes. Eventually, I glanced to the right to see if the mother was near and when I looked back a millisecond later, the baby fox had vanished.

• Two antelope does watched the sunrise with Charlie yesterday morning. Antelope have never been so close to the house!

• Sometimes, when I’m caring for a calf, which, sometimes, is not pretty or graceful or easy, the calf will be like, “You’re scaring me you’re hurting me PLEASE STOP!!!!” and I’m like, “Baby, I’m trying to SAVE YOUR LIFE!” Sometimes, my own life feels so painful and terrifying and I’ve just started wondering if hmmmmm, what if the powers that be, powers bigger and stronger than myself, are trying to help me out, it’s just that from where I’m at, it feels like an attack. Part of me writes this off as wishful thinking. But when I let myself believe it, it feels so good to be taken care of… even if it hurts.

A Black Baldy And A Book

When a black Angus cow has a white face, she’s called a black baldy.

And sometimes, her calves are baldies, too!

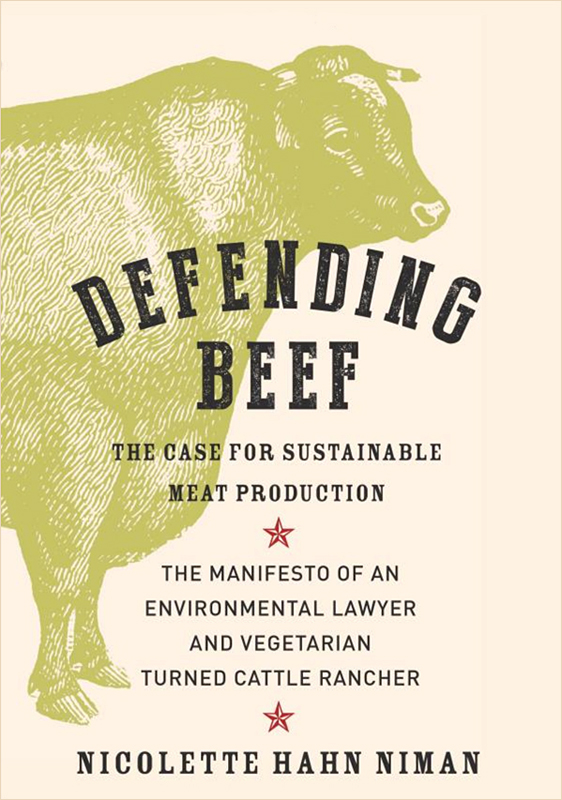

An important book: DEFENDING BEEF, written by vegetarian and environmental lawyer Nicolette Hahn Niman. This book is not a rah rah eat more meat echo chamber. It is a dense but easy-to-read powerhouse of a book filled with science and history, biology and ecology, and a smattering of politics to top it off. The section on soil is pure poetry… I mean it!

If you’re vegetarian or vegan and care about the environment, you should read this book. If you eat meat and care about the effects of your choices, you should read this book. Basically, anyone who eats food should read this book. Find it HERE or at your local library.

Dispatches From A Bovine Midwife

Calving season has been intense this year and I’m either out midwifing cows or recovering from midwifing cows (I got rolled down a snowy hillside by a cow with PPD when I rescued her calf from her headbanging; it’s been a week since then, and all three of us are doing fine, and she is now a wonderful mother). So, I haven’t been on the computer much. I sent the following story to the Star Brand Beef newsletter group the day after the Spring Equinox and, since I don’t have a post prepared for this week, I’m sharing it here, too!

. . .

Last night, I said to Mike, “I feel like I got nothing accomplished today.” And he replied, “You saved a calf’s life, I’d say you had a pretty successful day.”

I’d spent most of my day squatting in the damp wind with binoculars, watching a heifer (first time mother) in labor. Sometimes, heifers need extra help, and sometimes, they ignore their calves at first. I knew the latter would not be an issue for Ixchel, the cow I was watching. She had been hovering around another cow’s calf while in the early stages of labor, licking it and mooing to it as if it were her own. She was ready to be a mother. But her labor was taking a long time, longer than usual, so I wanted to watch her closely without getting in her way.

Crouching in the dirt, not knowing if what I was facing was going to be beyond my level of expertise, my heart beat ever-more-nervously as Ixchel got closer to delivery. I had my cell phone tucked into the shaft of my muck boot in case I needed to call for backup. When the calf’s hooves emerged, I knew things were leaning in a positive direction because the calf was not breach. And I also realized why Ixchel’s labor had been more prolonged than usual – her water hadn’t broke, and her calf hadn’t burst through the amniotic sac. Her calf was being delivered while still inside the amniotic sac! In humans, this is called an “en caul” birth and is quite rare.

Once the calf’s front hooves were out (though still enclosed in the amniotic sac), Ixchel lay down and began pushing in a slow, steady rhythm. The moment the calf’s head and shoulders emerged, I dropped my binoculars in the dirt and sprinted over to Ixchel and tore open the amniotic sac with my hands. I cleared the membrane and fluid from around the calf’s nose and mouth just as Ixchel pushed again and the calf’s rib cage emerged – when this happens, the baby is compelled to take its first breath. And if this calf had done so while still enclosed in the amniotic sac, she would have suffocated or drowned. But happily, she took a big breath of air and, with one last push from Ixchel, slithered out, wide eyed and perky. Birth is so wild.

Ixchel immediately got up and mooed a lullaby to her new baby and began licking her off, licking and licking and mooing and mooing. I got no paperwork or office work done, but I got to spend the day where it mattered.

. . .

PS: For a full-circle experience, you can read the story of Fiona giving birth to Ixchel HERE.

PPS: You can sign up for the Star Brand Beef newsletter HERE.