And Then There Were Kittens

Feral Kitten Girl arrived at my door one sunny autumn day, as had become her custom, but this time, she had her four kittens in tow. And she didn’t leave again. The kittens had a nest under my deck to which they would flee if they were frightened, but most of their time was spent exploring my home and the immediate surroundings, or sleeping in a pile: inside, on a huge pillow beside my desk, or outside, in the sun beside the woodpile. Feral Kitten Girl luxuriated in doing a whole lot of nothing, her responsibilities having dropped down to nursing. She’d gaze at me with a look of blissed out gratitude: “thanks for the food, for the safe haven, for watching my babies for me…. and now I’m going to take another nap.”

Eli, in contrast, was DISPLEASED.

Nevermind that they were probably his kittens (please don’t yell me an email about neutering Eli, it’s a waste of time. Eli has me under mind control. Though he has said when they start performing reversible vasectomies on all 16 year old guys, he, too, will have the procedure).

Though the four kittens and their mama worshiped Eli and eagerly surrounded him when he came home each morning, Eli responded to their swarm with a vicious hiss as he sprung over them in a flying leap to the stairs, and, with another great leap, escaped to the relative peace of the loft.

Some people assume that Eli is not an affectionate cat because he is so tough, but in truth, Eli loves attention. He needs it. I made a point of keeping Eli’s Love Quota steady and certain, and, thankfully, within a month, he had warmed to the new residents, and it soon became common to find them all napping together on my bed.

Feral Kitten Girl was no longer an appropriate name. It was never a proper name and now even more so, as she was no longer feral and, a mother many times over, no longer remotely a kitten or a girl. I named her Rue, short for Ruger. Beautiful Rue.

The kittens got names as well. There were two males: one solid black and the other a gray on gray stripe; and two females: one a soft mottled gray and the other tan and black tiger striped.

Gray girl had, from the very beginning, an absolute handful of flub ~ extra skin and fat and fuzz at her belly between her hind legs ~ which was (is) so much fun to smush. I started calling her Mushy. Though I’ve noticed very few people pronounce her name properly. It is not “mushy,” with the vowel sound of “LUSH.” It is “Mushy,” with the vowel sound of “PUSH.” Mushy! She looks like a cartoon in every way.

The other female was also quickly named. Her name is Kettle. Months before, Mike had found an old cast iron kettle out in the hills and, knowing I love that sort of thing, lugged it home for me. I keep it next to my woodstove and throw all my paper trash in it to use as firestarter. Kettle loved to climb into the kettle and curl up inside and sleep. Mike called her ‘the kettle kitten’ which I shortened to “Kettle.”

As for the boys… in the early days, I always referred to the black one as “the black one,” and then, one day, Mike remarked how the other male, the gray striped one, was “so gray he was practically blue.” And it was true ~ his fur was a cool, steel blue color. And so I declared the boys would, henceforth, be called Black and Blue.

I wanted to take Rue and all the kittens in to get spayed and neutered once the kittens were old enough to be weaned, and before they went off to their new homes (which turned out to be not much of an adjustment ~ Black and Blue now live with Mike; he’d been wanting a kitten for ages and I told him he really should take two, so they would have company, and my sister was going to take the girls but she changed her mind so they are here with me, along with Rue and Eli, and it’s hard to remember life before they were a part of it; I’m so glad she changed her mind).

However, in that tiny space of time between the kittens being weaned and my getting them all to the vet, I noticed Rue’s belly starting to get round and full again! “HOW did she manage to get bred again so fast, and without my noticing?” I thought to myself. I couldn’t believe it. But there she was, getting rounder and rounder by the day. And so I started feeding her more ~ raw meat, endless dry food, and treats ~ to make sure she stayed nourished through her pregnancy.

She got HUGE. Her head and hind legs remained dainty, but her body was a sphere. Mike called her Mama Football. I prepared a nesting box for her, filled with blankets, which she rarely left. Mike and I were certain she was going to have her litter any day. And then she went into heat. Which, if you’ve ever witnessed, is impossible to ignore or mistake for anything but a cat in heat.

Rue was not pregnant. She was obese!

I called the vet and got them all in immediately and, when I explained that Rue was a feral who had adopted me, they said they would check her teeth to determine her age. I kind of brushed it off, thinking she had to be about three, since she was so, so small when I first met her at the corrals. I was wrong. She is seven. She lived hard and rough for seven years. And now she has it made. But she is on a diet.

This Is Only A Test

My EMT class convenes, early Saturday morning, at a wrecking yard. We are joined by the Fire Department dressed in bunker gear. We’re here to practice extrication: safely removing people from vehicles be they stable, mangled, or flipped (the vehicle, that is ~ we always assume the patient is mangled).

While the Fire Dept practices stabilizing automobiles, we practice moving patients out from various cars and trucks and onto a backboard. I play ‘patient’ at one point and am awed at how smoothly, thanks to proper knowledge and teamwork, I am transferred from wrecked truck to backboard to ambulance.

We join up with the Fire crew to learn about the fearsome tools they use to take apart a vehicle. We watch them in action.

Cutting the A-beams for roof removal:

The top of a truck is folded forward:

After a morning of practice in 30ºF weather with unrelenting 20-mph wind,

“Just like the real thing,” one instructor sadistically cackles, we are corralled in the ambulance as our instructors set up a crash: two vehicles, one on its side, with four moulaged patients trapped inside. Moulage: gory makeup that simulates all sorts of wounds and injury.

My classmates and I, and the Fire rookies, are then called to the scene to assess, extricate and transport these patients, while also tending to the additional patient care that takes place during each stage. The patient I am responsible for is in the backseat of a Bronco, the upright vehicle in the crash.

I have a fireman break the back window of the Bronco for me and I crawl in to manually stabilize my patient in the backseat. I discern his status, talk with him; sometimes, as he drifts out of consciousness, I simply talk to him. I stay with him while others cover us with a tarp, and then I hear all the windows being broken in quick succession. The glass patters against the tarp; gleaming bits bounce under the hem where I kneel. Once the windows are broken, firemen work to cut away the roof.

Forced into blindness to all that is going on beyond the tarp I am under, the world becomes momentarily muted, then punctured by din as massive tools held by those I cannot see snap through steel just inches away from my patient and I. Others, recognizable by voice, shout questions to me, instructions to each other.

A pool of fear spreads inside me as my range of sight shrinks. I cannot see the rookies, wielding their bone crushing tools; I cannot participate, or even prepare myself for what might go on beyond this blue cocoon. I give myself a mental shake, and let go of everything I cannot see and give myself to the one thing I can: the patient I am with.

It comes down to trust.

Sometimes, that is all we have.

I give my trust to those who move unseen on the other side of the tarp,

so that my patient might trust in me.

My brain is….

after 12 hours of work in the ER

and 6 hours of EMT class

4 hours of commuting

in 3 days.

Birth & Death

One morning last week or the week before, Mike showed up at my house at 7am. He had a meeting a quarter way across the state that he had to attend and he was stopping by to give me the morning cow report since I would be the only one on the place overseeing any births that day.

Calving had been going incredibly well, with most of the cows calving between 11am and 1pm, and only a few as early as 6am or as late as 6pm. Only one heifer had needed assistance with her birth, but she was an unusually small cow, which was why she needed help getting her baby into this world. I knew I’d be holding down the homestead all day but did not expect much work other than strolling through the cows every couple of hours as they grazed on hay and lounged about.

Mike burst that bubble when he arrived with the following information: “Two heifers calved this morning, one pair is fine, the other calf isn’t up – I found it with the sac on its face and pulled it off and it took a massive breath but hasn’t been up to suck yet – and another heifer is prolapsed but hasn’t calved.”

Translation: Two first-time mothers had their babies. One pair (mother and calf) were fine but the other calf had not been cleaned off by its mother, and the calf could have died of suffocation as the water sack was still covering its face. Mike saw this and pulled it off, but had to leave before he saw the calf get up and drink successfully, but he did note the number of the cow standing beside this calf so that I could observe. A third first-time-mom was prolapsed; this means her guts had come out of her body during labor.

And then he was out the door, with a long drive ahead of him.

I said a swear word in my head and pulled on boots and a heavy coat and hat and scarf and grabbed leather gloves – it was a chilly morning but, worse than that, it was really windy – and hiked up to Mike’s house. I found the calf and a very disinterested heifer standing next to it and her number matched the number Mike had given me. The calf was stretched out on the ground – it’s head was not up – this is not a good sign. I checked to see if it was still alive and it was, it was still breathing, though its breaths were labored and it was still completely wet – this, too, is not good when a calf is weak to begin with and the morning is cold and windy.

But, before I could attend to the calf, I had to see the prolapsed cow. I had called the vet as I was getting dressed and he said that if I could get the cow to the corrals and contain her, he could come by and put her back together and everything would probably turn out just fine. When I saw the cow, I knew that plan would be impossible. Even though she was lying down, I could see the mass coming out her body was simply too large. It would have been painful and dangerous to have her walk down to the corrals, especially because there was one unavoidable stretch of sagebrush and weeds that could have easily caught or punctured the mass of guts that would have trailed behind her.

I knew she needed to be transported via trailer but I was certain I couldn’t accomplish that task on my own. So, THIS GUY and his neighbor came to the rescue. They pulled up with horse trailer in tow (with a saddled horse inside) hopped out, scoped the scene, and in half a minute, they had a plan in place. While M bridled his horse, S drove the truck and trailer into the field, not twenty feet from the cow, and backed it perpendicular to the fence. M opened the back of the trailer and made sure the door fit snugly against the fence, creating an L shaped corridor along the fenceline and into the trailer.

As M approached the prolapsed cow on horseback, she stood, and calmly walked the fenceline to the trailer. She then had to turn and enter the dark trailer, and balked, but I bounced into her intended path and she stopped, calmly reconsidering her options. M threw a large, easy loop with his lariat around the cow’s head and chest, but he didn’t cinch it – it just sat loosely around her, ready to be tightened if she decided to make a run for it in the wrong direction. S cooed at her, urging her to take a few steps forward again and step into the trailer, and she did just that. M wound up his lariat, loaded his horse in the compartment behind her, gave me wink, and off they went.

M was headed to the sale barn in town, which is where the vet was spending the morning preg testing cows, and he offered to drove the cow to town and hand her off directly to the vet. The time spanning their arrival to their departure was less than ten minutes. These guys are pros, and it was simply beautiful to watch them work with such calm competence.

I then turned my full attention to the calf. This calf was large ~ not abnormally large, but closer to 100 pounds than 70 pounds and I couldn’t carry it. I had to move it out of the wind, so I used my one of my newly acquired EMT emergency moves. I ran to Mike’s house, got a sheet, laid it beside the calf, flipped the calf onto the sheet, and dragged the calf to shelter. I sat beside him with his head in my lap and dried him off, got him warmed up, and tried to figure out what exactly was wrong with him.

The calf was having a lot of trouble breathing. He also had some sort of deformity with his head ~ I couldn’t put my finger on exactly what was wrong with his head, visually, just that something was very, very off. He did not move easily on his own ~ his limbs were stiff and uncoordinated and his tongue was thick and heavy, filling the side of his mouth. He did not have the sucking reflex when I put my finger in his mouth, and his tongue kept sliding into a weird position which further blocked his airway. (EMT trivia! A child’s tongue, in relation to the mouth, is proportionately larger than an adult’s tongue, therefore, it is more likely to cause airway obstruction and hinder respirations)

Everything about this calf seemed like the result of poor perfusion (EMT vocab term! lack of oxygen and buildup of waste material at the cell level) As I sat in the dirt with the calf’s head on my lap, I wished I had an oxygen tank and mask. I totally would have put it on the calf. Instead, I continued to rub the calf and talk to it, and then, perhaps an hour later, seeing no change in the calf, I left it on the sheet and walked home, checking the rest of the cows. It was either going to live or it was going to die.

I tried to work for an hour and then I ran up to Mike’s to check on the calf again. It was still laying down all the way, but it was breathing. What I found odd and irritating was that it’s mother was completely ignoring it. She was on the other side of the pasture, sleeping. Sometimes, a heifer will ignore her baby, but it really is rare. This cow’s complete lack of attention to this calf struck me as off, too, though I couldn’t place why.

I sat with the calf and talked to it some more, and it managed to hold it’s head up for short periods of time. His sucking reflex was evident, too, though it was quite weak. Both these developments made me extremely hopeful. I went to Mike’s house and prepared a bottle of Daisy’s colostrum milk that I had frozen when Frisco was born (she produced more than he could drink), and tried to help the calf drink a little. But it was difficult, as the calf was still so weak and uncoordinated, and he only drank, at most, a few tablespoons.

After a while I went back home, and while I was there, the vet called. The cow was dead. Everything had gone fine ~ he had put her back together, stitched her up, and the cow had been stable under anesthesia, but when the vet gave her a shot to bring her out from anesthesia, her heart stopped. “You’ve got a dead calf out there,” he said, as we were ending the call. “What?” I asked, totally confused. “She calved already,” the vet told me; “she calved during the prolapse. So her calf is out there, but it’s probably dead.”

I ran back up to Mike’s house. I scoured the pasture and draws, looking for a dead calf, and found none. I tracked down the cow that Mike had said was the mother to the calf I had been nursing all morning. I looked at her udder. It was small, and, while a heifer can have a small udder, hers was definitely not full enough to indicate having calved. “I bet this calf is the prolapsed cow’s calf!” I thought to myself, very pleased with the thought. I was heartbroken that the cow had died but was determined to keep her calf alive.

When Mike finally called on his drive home, I asked him if he had seen the birth of the calf in question or not. He had not actually seen it happen ~ he had just seen the obviously-newly-born calf with a heifer standing next to it and, in the rush of the morning, assumed it was its mother.

When Mike got home, he carried the calf – who had still not been able to stand up all day – into his house and built a fire. I sat on the floor in front of the fireplace with the giant newborn calf on my lap, and, as it got warmer and warmer, the calf seemed to get stronger and friskier. I pointed out the head deformity to Mike, who was able to pinpoint what was off ~ there was a puffiness around the calf’s throat and jaw, most likely lividity – the settling of fluids – that probably occurred during the difficult birth. (This completely disappeared within days.)

I warmed up the bottle again, and this time, the calf drank it all! He even stood up and was able to teeter around. Mike and I built a playpen of sorts out of furniture, effectively penning the calf in a small area in front of the fireplace for the night, and though he was still somewhat weak the next morning, his vitality and coordination were steadily improving.

This will seem like a tangent, but it’s not: Mike’s cows are numbered; the numbers have meaning (birth year, linage) and, while this might seem impersonal, Mike and I know all the temperaments and personalities and quirks of each cow; their numbers are like names to us. Kind of like that couple who named their dog Diogee.

There’s a cow whose number-name is 412, and I have always been acutely aware of this cow’s goings-on, because she’s my birthday cow. Her number is my birthday. She’s like my sister-cow. 412 had given birth two days prior, to a stillborn calf. This isn’t terribly common, but it is terribly sad. 412 could not accept that her baby was dead. She stood under tree where she had given birth, guarding the tiny corpse, nudging it periodically, urging it to come to life. She would not leave her calf. She had held vigil for two days and counting.

Since the days were still cold, we left the calf where it was, with her. There was the outside possibility that twins would be born in a matter of days and, since cows generally only raise one, orphaning the second, we could give one to 412 to raise. Twins were not born, but we now had an orphan calf.

The next morning, Mike rode his 4-wheeler down to 412, snatched up her baby, and drove to the corrals with 412 hot on his heels. He put her into a small stall. We then drove the orphan calf down to the corrals. While I held him, Mike quickly skinned 412’s dead calf. We cut holes in the four corners of the pelt and fit the orphan baby’s legs through these holes, the pelt covering his back. This is called ‘jacketing.’ A mother cow knows her baby by smell, and will not let any other calf drink her milk. We had to make 412 believe that this new calf was really her calf. That is why we gave it the ‘jacket’ of the dead calf.

We put the calf in with 412 and she rushed to him, mooing gently, licking him, absolutely in love. It was her baby! And she was A-OK with him nursing her. He latched on and drank till he was full. Two days later, we removed the jacket; by that time, 412’s milk had circulated through the calf and his scent was hers. And they are a pair, and it is a beautiful sight, especially as it had been borne from dual tragedies.

Moonbath Multitask

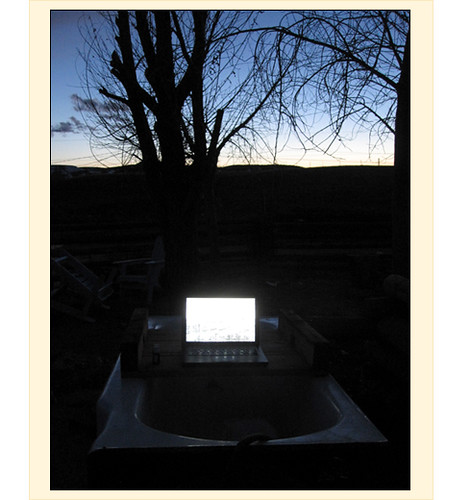

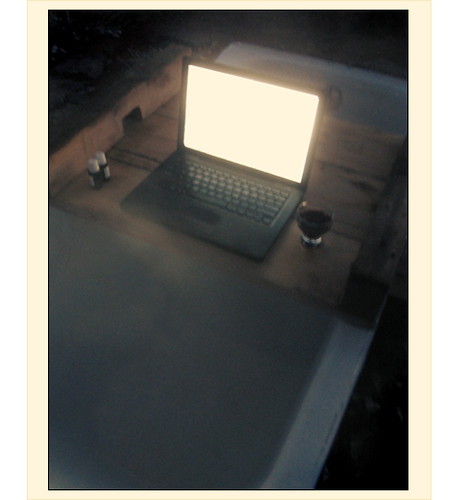

These days, I have had zero time for unadulterated relaxation. Between cows calving and EMT class in high gear and that thing called work and animals to attend to, I’ve taken to mixing respite and responsibility in equal portions ~

an hour spent stretched out on my bed (reading my EMT book), romantic dates with Mike (while feeding cows).

Last night, I prepared to do some much needed writing whilst soaking in my steaming hot, deluxe outdoor cast iron tub. I rigged up some nice pine boards as a sturdy shelving apparatus to keep my laptop dry and a glass of wine and essential oils within easy reach.

When I slipped in, chin deep under the stars, I closed my laptop; ignored the wine. I sank into unadulterated relaxation. The sky darkened to deepest indigo, and stars glided toward distant horizons, and the steam curled the loose tendrils of my soul, restoring buoyancy, sending them free.

« go back — keep looking »